It could be the title of a book or a movie. Instead, it’s what really happened: eleven years of relentless activity, orbiting one and a half million kilometers from home. Billions upon billions of measurements, sent to Earth daily.

But let’s start from the beginning.

I’ve written about the ESA’s Gaia spacecraft many times on my italian blog (or rather, we have, because my dear friend and skilled science communicator Sabrina Masiero has contributed with some of her numerous articles). And it all started well before the launch.

Now that it’s ending, I find myself reflecting on it.

To be precise, Gaia first appeared on my blog (back then called GruppoLocale) more than ten years before its launch, in a 2002 post titled The Gaia Spacecraft and the Models of the Milky Way. A decade before the launch, at a time when I had no idea I would eventually be involved in Gaia’s work, dedicating many, many years to it.

There was no Media INAF (the official website for astronomical news from Italian National Institute of Astrophysics) back then (which would only begin covering Gaia in 2011, almost ten years later), and there weren’t as many sources to draw space-related news from. So I simply thought it was important to write about it, to help bring extraordinary projects like this beyond the realm of specialists. I wrote about it, of course, as someone in the field, but without any direct involvement in the mission.

How funny. How many things I didn’t know (but we never truly know what lies ahead, do we?). Just a few years later, I would find myself part of the working group forming at the Observatory.

Gaia’s work involved (and still involves) hundreds of people (scattered across Europe but united under the DPAC). Each had specific tasks. The one assigned to us – as I soon discovered – was managing the spectral profiles of stars in crowded fields. In simpler terms, it was about reconstructing the stellar spectra recorded by Gaia in areas of the galaxy where density is high (typically, the core of a globular cluster or the very center of the Milky Way). This task was carried out alongside much of my life, with its joys and struggles, shared with Luigi Pulone and Giuliano Giuffrida, and often with Anna Piersimoni and Fiore de Luise from the Abruzzo Astronomical Observatory. Friends, before colleagues.

Looking back, it’s because Gaia is nearing retirement. After nearly double its initially planned operational time, Gaia is ceasing its scientific observations today, following a long-established plan, and transitioning into a heliocentric orbit where it won’t interfere with anything. At some point, in a few months, it will be completely deactivated.

Even after stopping scientific observations, Gaia won’t immediately cease all operations. The opportunity to utilize a spacecraft that’s been active for over a decade is too valuable. Gaia will embark on a series of technical tests over several weeks, potentially benefiting future missions. It will then be fully decommissioned between March and April of this year, finally free from all obligations to Earth and able to fully enjoy space, perhaps reflecting on the countless things it has revealed to us – about the Milky Way and much more (planets, quasars, asteroids) – over all these years.

Reflecting on it, it was a demanding and multifaceted task, now naturally coming to an end. There were moments of exhilaration (like seeing our work highlighted as Image of the Week) and moments of despair (which aren’t very useful to dwell on), as is normal.

I’ve learned a lot from my experience with Gaia. And I believe that’s the most important thing.

I’ve learned, with time, what it means to work in a large team, the need for regular reporting, scheduled meetings, and annual workshops. I’ve met people, seen places, and encountered new ways of thinking. I’ve visited other scientific institutions, shared coffee, climbed stairs in distant places, fought my fears, and pushed myself. I’ve faced the fear of inadequacy countless times, confronted and managed the tensions that arise when different approaches to a task collide. Responding to an inner urge, I also tried to turn part of what I experienced into a story. My (so far, unique) novel, Il ritorno (“The Return”, in English), owes a great deal (though not everything) to my time with Gaia.

I’ve seen how a team of hundreds can carry forward a massive project (divided into countless sub-projects like tributaries of a great river) without losing its way. I’ve shared the excitement and anticipation of the first, second, and third data releases. I’ve also seen personal interests intertwine with shared goals, passion, uncertainty, kindness, and detachment. I’ve realized we, the Gaia scientists, are human too. And no spacecraft is worth it if it doesn’t help us touch – anew and in new ways – our humanity, which always shines brighter than any star in any galaxy.

Eleven years in space were also eleven intense years on Earth for many of us. Eleven years in which we’ve changed greatly, no longer the people we were. Not only because we know the Milky Way much better than we did when Gaia first launched, but because we’ve come to know ourselves better. We’ve tested ourselves and contributed to a shared endeavor, where differences don’t have the final word but are sometimes painfully set aside for a shared goal. In the end, the simple sense of it was worth it prevails.

Goodbye, Gaia. Thank you for the human adventure you’ve let me experience. Thank you for the frustrations, doubts, and moments of boredom. Thank you for all the pains and uncertainties that made the journey more real and less idealized. For the countless opportunities for connection you created, especially for me. For giving me the chance to better understand who I am and what I genuinely want. Without all this, I would undoubtedly be something less than I am today.

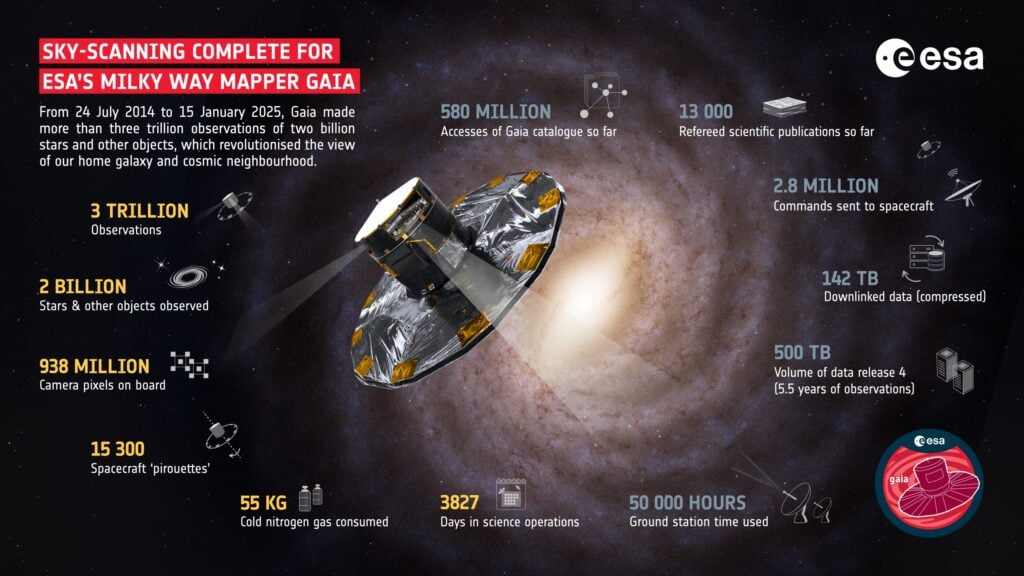

Cover of the post: artistic image of Gaia spacecraft (Credits: ESA)

Translated & adapted from italian, with the help of an AI assistant

Such a remarkable journey, both in space and personally! The insights shared about the Gaia mission are truly inspiring. It’s incredible to think about the immense impact of such a long-term project—not only on science but also on the individuals involved. The reflection on how working on Gaia helped you learn about teamwork, overcoming personal fears, and understanding your own humanity adds a powerful human touch to the story. Wishing the mission and the team all the best as it transitions to the next phase!

This article beautifully captures the human spirit behind such a monumental project! It’s inspiring to see how Gaia not only expanded our understanding of the cosmos but also connected people on a deeply personal level. The dedication of the team over these 11 years is a testament to how collaborative efforts can achieve extraordinary results. Speaking of remarkable journeys, I recently came across an article on BitLife challenges that offers an interesting perspective on decision-making and life simulation: https://bitlifeappspro.com/. It’s fascinating how both real-life missions and virtual experiences can teach us so much about persistence and discovery.

Hi Marco, I really enjoyed your web page on Gaia, it brought back so many memories for me!

I would like to add the following four lines (well, eight, we are still astronomers), proudly written by hand several years ago with a flexible nib, and still relevant today!